|

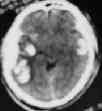

A hematoma within the brain parenchyma is known as

intracerebral hematoma. Although it is difficult to define whether it is

contusion or true ICH, it has been reported that they make up at least

30% of all intracranial hematomas.

Etiopathogenesis:

They result from bleeding from damaged vessels deep in the

brain following a trauma.

Acute ICH is mainly of primary type resulting from

arterial bleeding.

When it results from damage to vessels of the brain surface

in the focus of cerebral contusion or laceration, it is called secondary

hematomas.

The majority of both forms occur on the site of cerebral

contusion-in the frontal and temporal regions. Initially they may be

small foci, small fusing bleedings. Hypoxia and acidification of brain

tissues enhance permeability of the vessels resulting in

intracerebral hematomas.

Toxic action of extravasated blood results in brain edema

and raised ICP. ICH may lead to coagulopathy due to release of

thromboplastin from the brain parenchyma.

The traumatic ICHs are most frequently occur in the

temporal, frontal, and parieto-occipital areas.

|

Clinical features:

Decreased level of consciousness, focal signs and symptoms

predominate.

Diagnosis is by CT or MRI scanning.

|

|

|

|

Management:

|

pri.traumatic ICH

|

sec.traumatic ICHs

|

A decisive factor in the management is the clinical picture.

If the GCS is between 3- 9 with no other obvious cause, most

surgeons recommend surgical evacuation and decompression, especially if

the ICH is easily accessible. Stereotactic aspiration is an emerging

technique. Other patients may be treated conservatively and monitored

periodically with serial CTs.

Multiple hemorrhages, especially bilateral, will not benefit

from surgical evacuation.

Aggressive medical management must accompany any surgical

intervention.

The final outcome depends on the preoperative status of the

patient.

|