|

Despite the progress in antimicrobial therapy, pyogenic

infections of the CNS remains a serious disease, with significant

mortality and morbidity. The neurosurgeon encounters these infections as

intra-cranial and spinal abscesses and post-traumatic and post-operative

infections. In addition, neurosurgeons are often associated with

management of bacterial meningitis.

1 ) Spontaneous bacterial meningitis:

Almost three-quarters of the spontaneous meningitis are due

to Streptococcus pneumoniae ( pneumococcus ), Haemophilus influenzae (

Haemophilus ) and Nisseria meningococcus infection; certain organisms

tend to predominate with the age of the patient.

|

New born:

|

Childhood:

|

Adult:

|

|

1) Gram negative

bacilli

|

1) Haemophilus

influenzae

|

1) Streptococcus

pneumoniae

|

|

2) Group B

streptococci

|

2) Neisseria

meningitidis

|

2) Neisseria

meningitidis

|

|

3) Listeria

monocytogenes

|

3) Streptococcus

pneumoniae

|

|

Pathogenesis:

Haematogenous spread is the most common,

either venous or arterial. The organisms appear to enter the CSF through

choroid plexus, aggregate in and around cerebral draining veins and

archnoidal villi and cause cerebral phlebitis and arachnoid villous

dysfunction which may lead to increased ICT. Pial cell necrosis, small

vessel arteritis and phlebitis are frequently associated.

Retrograde propagation ( infected thrombi

within emissary veins ) from sinusitis, otitis and mastoiditis and direct

spread from trauma and adjacent infective foci are other modes of

infection.

Clinical features:

The typical symptoms include fever, headache, photophobia,

stiff neck, nausea and vomiting, lethargy or altered mental status.

On examination, in addition to fever, there may be rashes (

meningococcus ).There may be resistance of neck flexion (Kerning's sign )

and passive flexion may cause flexion of hips and knees (Brudzinski's

sign ). Altered sensorium and focal neurological deficit may be noted.

Infants do not usually have neck stiffness.

Examination should also include a search for a primary

focus, such as mastoiditis, sinusitis, otitis and endocarditis.

Diagnosis:

SAH and Neuroleptic malignant syndromes are sometimes

confused with meningitis. Very occasionally a posterior fossa tumor may present

in a similar way. Tuberculous and Viral meningitis may have to be ruled

out only by investigations at times.

Direct examination of the CSF provides the diagnosis.

Decrease in glucose content, elevation of proteins and polymorphonuclear

leukocytosis are the expected findings. A relative increase in

mononuclear leucocytosis or lymphocytes may suggest viral or tuberculous

etiology respectively. Organisms may be detected on a Gram's stain

and grow in culture and their antibiotic sensitivities are essential

for management. AFB staining should be carried out as a routine in these

days of AIDS.

Additional tests such as blood cultures and

counterimmunoelectrophoresis or agglutination tests may help when partial

treatment prevents the growth of bacteria in culture. A lactate content

of more than 3.8 mmol/l in the CSF and C-reactive protein greater than

100 ng/ml will also help in differentiating bacterial from viral

meningitis.

|

A mild diffuse

rise in ICT is common in meningitis and should not prevent a lumbar

puncture. Decrease in the level of consciousness or a focal

neurological deficit suggest presence of increased IC in most. Absence

of papilledema does not exclude a significant increase in ICT.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subdural empyema-rt.frontal&

parafalcine

|

Cerbellar

-epidural abcess

|

Meningeal

enhancement-CT

|

When suspected, associated intra-cranial abscess or

hydro-cephalus, should be ruled out with CT or MRI scan.

Imaging with CT and MRI is useful in evaluating the leptomeningeal

involvement and complications of meningitis.

Treatment:

Adequate antibiotic therapy, initially empirical, then

according to culture studies is the treatment.

Empirical antibiotic therapy is based on epidemiological

information, age and CSF gram's stain studies and should be started with

broad-spectrum antibiotics. Intrathecal and intraventricular instillation

may be reserved for systemic treatment failure.

Other appropriate supportive management is mandatory. Surgery

may be needed to tide over a crisis, such as hydrocephalus.

Uncomplicated cases require 2 weeks of antibiotics following

a satisfactory response.

Recurrence within a few weeks should prompt a search for a

persistent focus or immune deficiency status. Careful examination for

anomalies such as congenital dermal sinus, enteric cysts,

encephalocele and meningocele is warranted.

2 ) 'Neurosurgical' bacterial meningitis:

Headache, nuchal rigidity and altered sensorium are less

reliable in meningitis in neurosurgical patients. Pre-existing

neurological deficits and effects of surgery may cloud the clinical

picture. They are characterised by different aetiology and require a

different management on occasions.

Post-traumatic:

Streptococcus pneumoniae is more often associated with dural

tears following skull fractures. Penetrating injuries may precipitate

Gram negative bacilli, such as klebsiella, E.coli, Pseudomonas and other

enterobacteriaceae.

Treatment includes surgical repair of the dural tear, in

addition to appropriate antibiotics.

Postoperative:

The incidence of postoperative meningitis varies between

1-15 %. The most common microbes involved were Pseudomonas, Klebsiella,

E.coli and rarely other enterobactericeae.

It is claimed that third generation cephalosporins at the

start of surgery reduce the incidence of post-operative meningitis.

Shunt infections:

The incidence varies in different series with an average of

10%. Staphylococcus epidermidis and aureus (the non pathogenic skin flora

) are often the culprits.

In addition to antibiotic therapy, the shunt may have to be

removed.

Congenital anomalies:

Ruptured meningomyelocoele or a persistent dermal sinus in

the craniospinal axis may be the cause for recurrent meningitis. Unusual

and mixed pathogens should alert the surgeon.

They require appropriate surgery in addition to antibiotics.

3 ) Epidural and subdural empyemas:

These are rare these days.

Epidural empyemas are often

associated with osteomyelitis of the skull. Frontal sinusitis, depressed

fractures and penetrating injuries are the usual causes. Aspiration of

these well localized collections and appropriate antibiotics give good

results. Associated skull osteomyelitis must be eradicated.

Subdural empyemas are an emergency. Paranasal

sinusitis is the common cause. Subdural effusions and hematomas may get

infected and become empyema. Aspiration and appropriate antibiotics is

the treatment. Attention to predisposing factors should follow

immediately.

4 ) Brain abscess:

Incidence is about 8% of the ICSOLs in India and on

the rise in developed countries as well with the advent of AIDS.

Pathogenesis:

Bacteroides and anaerobic streptococci are the most common

causative bacteria.

The majority of them are caused by spread from adjacent

sites. Frontal and ethmoid sinusitis can lead to frontal abscesses,

maxillary sinusitis to temporal lobe abscesses, sphenoid sinusitis to

frontal or temporal abscesses, and mastoiditis to temporal lobe or

cerebellar abscesses. Abscesses from the sinuses are commonly caused by Streptococci.

Those of otic origin is mostly by a combination of aerobes

and anaerobes and is the commonest cause in India.

Trauma, especially with retained foreign

bodies, is also a significant cause. Staphylococcus aureus is

often the causative organism.

Metastatic abscesses from a remote

site are by hematogenous route, the commonest cause in developed

countries. They are often multiple and typically occur at the junction of

the white and gray matter, where the capillary blood flow is the slowest.

They are more commonly seen in the distribution of the middle cerebral

arteries and the parietal lobes, where the regional blood flow is the

highest. The common systemic sites are chronic pulmonary infections, skin

pustules, bacterial endocarditis and osteomyelitis. Those with a right to

left vascular shunt as a result of congenital heart disease or pulmonary

arteriovenous malformations are particularly susceptible. These abscesses

contain a mixed flora.

In about 25 % of patients, the source is unknown.

As the infection reaches the brain, there is immediate

inflammatory response with edema and increased vasculairty;

thrombophlebitis may block venous drainage and edema worsens; small

vessels get thrombosed; areas of necrosis appear; reactions from the surrounding

brain form a capsule and the infection get localized as the capsule gets

thicker.

It is suggested that there is early cerebritis on days 1 to

3, late cerebritis on days 4 to 9, early capsule formation on days 10 to

13, and late capsule formation after day 14.

Meningitis may precede or complicate an abscess. An abscess

may rupture into the ventricles causing ventriculitis which is often

fatal.

Clinical features:

They mimic any other ICSOL with seizures, focal deficits and

features of raised ICT, such as headache, vomiting. There is no specific

feature. Low grade fever may be seen in some, especially in early stages.

Associated causative conditions may suggest an abscess.

Diagnosis:

Suspicion is the first step.

There may be leucocytosis in early stages; ESR is usually

raised; plasma C-reactive protein is elevated.

CT scan reveals a contrast enhancing ring lesion with

non-enhancing hypodense center and surrounding edema. There may be gas

inside the lesion and ventricular and meningeal enhancement.

|

|

|

|

|

|

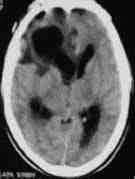

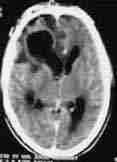

frontal

abscess-plain CT

|

frontal

abscess-contrast CT

|

frontal

abscess-ruptured into ventricle-plain CT

|

frontal

abscess-ruptured into ventricle-contrast CT

|

MRI scan delineates the lesion better and also reveals

additional micro-abscesses, if any.

Isotope scan and PET (positron emission tomography ) scan

may be of help to differentiate between an abscess and a tumor with

necrotic

center.

Treatment:

The management is still a controversial topic. Some studies

suggest that with adequate antibiotic therapy, mortality rates (10 to

20%) are similar after aspiration alone, or aspiration followed by

excision, or primary excision.

It is widely presumed that total excision reduces the

recurrence rates and the incidence of seizures, but there is no evidence

to support this .But excision does shorten the hospital stay and the

antibiotic therapy.

Surgical therapy:

Surgery establishes the diagnosis, removes the infected, and

necrotic tissue, provides the material for microbiological studies, and

relieves raised ICT.

The recommended procedures are aspiration, excision and

drainage.

Drainage using a flexible drain is seldom

used nowadays and has been replaced by aspiration and excision

procedures.

Total excision is a must in abscesses containing

foreign material. Excision may be the primary procedure. Some prefer to

aspirate, get the culture studies and excise the lesion after few days of

appropriate antibiotics. Studies suggest that such preoperative

antibiotics are of little benefit. The location and the stage of abscess,

the condition of the patient need to be considered in choosing between

aspiration and excision.

Total excision is not feasible if the capsule is not well

formed or in deep and critical areas without significant morbidity and

also in seriously ill patients. In such cases, stereotactic aspiration

is recommended and it is also useful in multiple abscesses.

Medical therapy:

Blind antibiotic therapy may be of use in ' cerebritis '

stage. There are occasional reports claiming cure with antibiotics alone,

either empirically or after blood and / or CSF studies, especially in

microabscesses. With the advent of stereotactic facilities it is not

recommended even in microabscesses.

Associated antiedema measures and other supportive therapy

are indicated.

Associated predisposing conditions should be eradicated.

Antibiotics should be continued for 6-8 weeks and patient

should be followed up for about 6 months.

5 ) Skull Osteomyelitis:

Most are related to trauma and spread from adjacent sites,

especially the frontal sinusitis. There are occasional case reports of

hematogenous origin.

In acute osteomyelitis, the patient is toxic with tender

swelling over the involved bone called " Pott's puffy tumor "

and likely to involve the CNS.

Chronic ones often present with a lump in the scalp.

Treatment is wide excision of the involved bone until the

normal bone is reached and appropriate antibiotics. Treatment of

associated condition should follow.

6 ) Bacterial infections of the spine:

It is uncommon.

The route of infection is hematogenous from usually the

urinary tract by retrograde venous seeding through Batson's venous

plexus, or direct extension from adjacent sites, or as a result of

penetrating injury. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism.

Gram negative organisms and anaerobes have also been implicated.

Iatrogenic causes such as post discectomy (1%), lumbar

punctures are rare. This should be excluded in 'Failed back syndromes'.

It usually affects two adjacent vertebrae and the disc.

Posterior elements are rarely involved. The lumbar and thoracic spines

are more commonly affected.

Acute infections present with fever, backache and tender

spines and the chronic ones with just pain.

Neurological complications, due to epidural extension and

spinal deformity and instability, may occur.

X-rays show disc space narrowing in early stages and

vertebral collapse in late stages with associated deformity.

Isotope and CT scans may pick up early lesions and the skip

lesions. if any.

CT guided aspiration and biopsy for diagnosis and

microbiological studies are widely practiced.

MRI scans reveal the extent of the intra spinal extension.

Treatment is bed rest until pain subsides and antibiotics

are administered for 6 to 8 weeks in uncomplicated cases.

Debridement, decompression and stabilization with bone

grafting is recommended when there is a progressive neurological deficit

and extensive vertebral or intraspinal involvement. Ideally an anterior

or anterolateral approach is employed unless there is posterior

involvement which is rare. Instrumentations are avoided.

|