|

Craniopharyngiomas are the

commonest of a heteregenous group of tumors that have in common their

congenital origin and slow rate of growth. They have always been one of

the most controversial problems of neurosurgery concerning their origin,

optimal therapy, operative approach, and response to radiation.

Craniopharyngiomas are still one of the most challenging tumors for

neurosurgeons. Despite the significant technical advances in

microneurosurgery, radiation therapy and endocrinology, the controversies

have not abated.

Controversies apart, for all

practical purposes, they are better considered as true neoplasms, rather

than an hamartoma or a cyst. Rightly, WHO has listed

them as sellar tumors, although purists may not agree.

Incidence:

Craniopharyngiomas

constitute between 2.5-4% of all intracranial tumors. There are 0.5-2 new

cases per million populations occurring each year. Almost 50% are in

adults. Craniopharyngioma is the most common tumor of non-glial origin in

children representing 54% of all suprasellar tumours in childhood and 20%

of those in adults.

They may present at any age

with preponderance in childhood. The highest peak of incidence is between

the ages of 5 and 10, a moderate peak exists among adults in the 4th and

5th decade. The tumor occurs with equal frequency in both sexes in all

ages.

Pathology:

Since the anatomical

structures in the suprasellar region are normally devoid of epithelial

cells such as those seen in craniopharyngiomas, the nature and source of

these cells have long been the subject of intensive investigation. In

1899, Mott and Barrett stated that Craniopharyngiomas may

arise from the hypophyseal-pharyngeal duct or Rathke’s pouch. In

addition, Erdheim demonstrated in 1904 that these are epithelial

tumors arising from embryonic squamous cell rests of the incompletely

involuted hypophyseal-pharyngeal duct located in the pars tuberalis and

along the pituitary stalk. This theory continues to be widely accepted.

However, since squamous cell rests are rarely found in neonates, and

their presence increases with age, some argue that these tumors are not

originated from those embryonic rests, but may arise by metaplasia of

normally developed anterior pituitary cells.

Craniopharyngiomas are

histologically benign tumors of epithelial origin involving primarily the

sellar region with a tendency to adhere to vital neural and vascular

structures. Although usually well circumscribed and extracerebral in

location, they often extend into the neighboring brain tissue evoking a

variable degree of glial reaction. They may also be strongly adherent to

major arteries and cranial nerves at the removal difficult and sometimes

impossible. Postoperative complications and tumor recurrence are

frequent. Consequently, this benign tumor is often malignant in clinical

behavior.

Craniopharyngiomas are mostly

located in the suprasellar region and grow by expansion into the

hypothalamus and third ventricle upwards, growing into the sella, down

between the clivus and brainstem, or even into the cerebelloprontine

cistern. There are some rare primary locations, such as: intrasellar,

within the third ventricle, nasopharyngeal, craniobasal, and pineal.

Occasionally they may be enormous. Occlusion of the CSF pathways with

subsequent hydrocephalus occurs in 15 to 30% of the cases.

The macrosocpic appearance

of craniopharyngiomas is wholly cystic in 34%, purely solid in 23% and

mixed in 43%, thus about 77% tumors are cystic. The fluid in these cysts

is oily yellow, brown, or greenish. This solution contains variable

amounts of protein with suspended cholesterol crystals which are

birefringent to polarized light is viscosity varies from watery to

viscous. Cyst walls may be transparent membranes or dense, tough

structures. Calcification is found in about half of adult

craniopharyngiomas and in almost all children.

Histology:

Craniopharyngiomas are generally composed of mature epithelial cells with

an external layer of high columnar epithelium, a variable portion of

polygonal cells and a central network of epithelial cells, without any

sign of malignant heterogeneity, cellular atypia or mitoses. This

structure is supported by variable amounts of loose growth of these

tumors is not neoplastic, but results from simple cellular proliferation

of the epithelium, desquamation, degeneration and colliquation of the

epithelial cells with active sequestration of cystic fluid. Regressive

changes in the epithelial cells include cellular liquefaction resulting

in cyst formation or deposition of a keratin-like material or calcium

salts resulting in calcification.

There are two basic craniopharyngioma

variants, the adamantinous and squamous papillary type. There is a

correlation between the histopathological, clinical, and prognostic

features of the two histological types. The behavior of childhood

craniopharyngioma is distinctly different from that in adults.

|

Adamantinous

craniopharyngiomas (48% of all cases) develop mainly in childhood, but

may occur in all ages. These are cystic, calcified tumors which are

prone to recur even after radical surgical removal and have a worse

overall outcome. They are characterized by a layer of palisading

columnar cells resting on a thin basement membrane with loose

aggregates of stellate epithelial cells in the middle. Central

degenerative changes are frequent, leading to cyst formation, keratin

nodule development and calcification.

Squamous papillary

craniopharyngiomas (33%) occur predominantly in adults. They are

chiefly solid, non calcified lesions with little tendency to recur

after total removal and thus a significantly better overall outcome. Microscopically,

squamous epithelial cells form solid nests or sheets embedded in a

loose connective tissue stroma.

Both the squamous

and adamantinous tumors may contain solid and cystic areas,

|

|

|

though their

proportion is usually different in the two types.

Beside these two

forms, a third, mixed type (19%) has been described. Because of

the frequent association of admantinous tumors with large squamous

epithelium-lined cysts, many investigators have suggested that

craniopharynigomas represent a spectrum of a single group of tumors,

with a range of characteristics from the purely adamantinous type

through a mixed variety to the squamous papillary type.

|

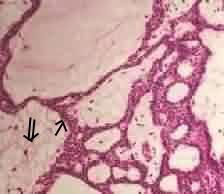

Adamantinous

craniopharyngioma (H&E): anastomosing cords of

predominately basloid epithelial cells(arrow) enclosing

areas of loose collagenous matrix (double arrow)

|

|

The histological

differences between adult and child hood craniopharyngiomas might

indicate separate origins. It has been argued that the pediatric

(adamantinous) group represents an embryogenic disorder and the adult

(squamous) tumor arises from metaplastic cells.

Craniopharyngiomas

do not invade neural tissue, but often cause an extensive glial

reaction at the interface, which is particularly dense around small

finger-like tumor projects toward the hypothalamus. Traction on this

tenacious attachment may lead to hypothalamic infarction and thus

preclude safe total removal of the tumor. In other cases this glial

envelope may provide a plane in which to dissect between the tumor and

the hypothalamic structures making total surgical removal possible.

Both features can be present in the same tumor.

Similarly,

craniopharyngiomas are frequently strongly adherent to major arteries

and

|

|

|

cranial nerves at

the base of the brain. The most tenacious attachments are to the stalk,

and the arteries of the anterior portion of the circle of Willis.

Adherence to these structures can vary from mere approximation to

persistent attachment preventing total removal in some cases.

|

Papillary

craniopharyngioma( H&E): squamous

epithelial cells(arrow)

form solid nests or sheets embedded in a loose connective tissue

stroma.

|

Symptoms and signs:

The clinical signs are due

to the location of the tumor, though adults and children may have

different clinical syndromes. The multiplicity of possible directions of

growth of these tumors is mirrored by a corresponding variation in the

clinical pictures they may present.

Children:

Since these tumors may reach a large size before causing symptoms in

children, they usually present with signs of increased intracranial

pressure mainly due to occlusion CSF pathways and secondary hydrocephalus

or due to the size of the cyst. Disturbances of hypothalamic-pituitary

function such as growth failure, pituitary dwarfism, hypogonadism,

delayed puberty, diabetes insipidus, genital dystrophy are also

characteristic in about 93%. Visual loss and visual field defects are

usually found at examination, though children tolerate remarkable degrees

of visual loss without complaint.

Adults:

Visual impairment and visual field defects (mostly bitemporal hemianopia)

are characteristic complaints in adults, but any combination of visual

symptoms can be present, similar to those of a pituitary adenomas.

Papillioedema is uncommon, but optic atrophy is frequent in both age

groups. Progressive visual failure requires urgent treatment in many

cases. Psychiatric symptoms include personality changes, dementia memory

loss, drowsiness, confusion, depression, hyperphagia, aggression which

can develop in association with obstructive hydrocephalus and with

hypothalamic dysfunction. Patients frequently (85%) present with

endocrinopathies such as menstrual irregularities, loss of libido,

diabetes insipidus, hypothyrodism, hypodrenalism, and obesity. Symptoms

suggesting intracranial hypertension often prompt patients to seek

medical attention. Spontaneous rupture of craniopharyngioma cysts is

extremely rare; only a few cases have been reported causing chemical meningitis

with temporary alleviation of headache and improvement in visual

disturbance.

Differential

diagnosis:

In Children: Hypothalamic

and optic gliomas, Germinomas, Hamartomas, Teratomas, Pituitary adenomas,

Histocytosis X, Chordomas, Ectopic pinealomas, Primitive neuroectodermal

tumours

In adults: Pituitary

adenomas, Rathke’s cleft cyst, Epithelial cyst, Meningioma, Epidermoid,

Dermoid, Arachnoid cyst, Cavernous angioma, Colloid cyst, Tuberculoma,

Metastasis, Internal carotid artery aneurysm.

Diagnosis:

There are a number of

neuroimaging methods to reveal the craniopharyngiomas surgically

important features as well as to differentiate them from other possible

suprasellar masses.

Plain skull X-rays show

pathological changes in most of the adult and almost all of the pediatric

cases. Tumor calcification is found on X-ray in 85% of the pediatric and

405 of the adult cases. Other signs include enlarged sella, bony erosion

of the sella, dorsum, or clinoids, and signs of increased ICP.

CT scan shows

the extent of the lesion, distinguishes between solid, cystic and

calcified components and demonstrates hydrocephalus. The appearance of

the cyst fluid is variable. It is usually of low density, but can be

isodense or hyperdense if it contains sufficient protein and suspended

calcium salts. The solid portions of craniopharyngiomas are either

isodense or slightly hyperdense. Contrast administration mostly causes

intensive heterogeneous enhancement. Ring-shaped contrast enhancement can

sometimes be seen around cysts. Coronal scanning helps to identify

intrasellar extension, relation to the third ventricle and impingement of

tumor on the basal brain parenchyma.

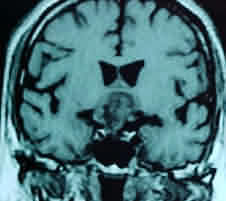

MRI is

superior to CT in demonstrating the general configuration of the tumor

mass, with us relationship to the ventricular system, major nerves and

cranial arteries. It characteristically shows a heterogeneous suprasellar

mass containing cysts and empty holes correlating with calcification.

Cysts usually appear bright on T2-weighted sequences. The signal intensity

of the fluid varies on T1-weighted images from hyperintense to hypotense,

reflecting the heterogeneous contents of cysts. Cysts with a low protein

content are indistinguishable from cysts of other etiology. Calcification

produces a low signal on MR images, which are less specific in this

respect than CT scans. Solid tumor components present a less well-defined

margins compared to pituitary adenomas. These areas intensively enhance

with gadolinium contrast on T1 weighted studies.

|

|

|

|

|

Craniopharyngioma-MRI- sagittal

|

Craniopharyngioma-MRI- axial

|

Craniopharyngioma-MRI- coronal

|

Angiography has

become redundant these days.

Management:

The treatment of cranipharyngioma

remains controversial, reflecting the difficulties in management as well

as the heterogeneity of these tumors. 15 to 30% of the patients require

attention to associated hydrocephalus.

In most cases,

cranipharyngiomas can be removed totally or subtotally even when they

have reached a great size. There is little doubt that an initial total

tumor excision yields the best long term outcome if it can be achieved

without neurological sequelae. Some workers regard surgery of

carniopharyngiomas as merely palliative and believe that subtotal or

partial resection followed by radiation therapy should be the rule.

While total removal may be

associated with significant endocrine alterations and hypothalamic

disturbances, subtotal removal results in higher rates of recurrence.

Most reviews conclude that

total excision should be attempted whenever feasible, and subtotal

removal with adjuvant radiation should be done when total resection is

dangerous. In cases of recurrence, radical tumor removal, subtotal

resection and/or irradiation are again the usual treatment modalities.

Adjunctive therapy should be

reserved for recurrent or predominantly cystic cases.

Strict

endocrinological evaluation and hormonal replacement regiments are

essential in all patients in both the immediate and long term

postoperative period. (refer

to pituitary adenoma)

Multimodality therapy is

often necessary over the course of a patient’s lifetime. Due to the

diverse nature of craniopharyngiomas, therapy must be individualized to

the particular clinical problem by following the natural history of each

case.

Surgical approaches:

There are several operative

approaches to craniopharyngiomas. Each has its own advantages and

disadvantages. The side of the craniotomy is determined by considering

various factors such as visual acuity and field defect, lateralization of

cyst, calcification and/or solid mass, lateralization of the compromised

hypothalamus, and the preference of the surgeon.

Unilateral

operations are preferable.

a) The pterional

(frontotemporal) approach provides access to virtually all parts of

even very large tumors. It is the shortest route to the parasellar

region and allows good visualization of the retrosellar area; but

visualization of the contralateral optic nerve is limited.

b) The

unilateral or bifrontal subfrontal approach allows good visualization of

optic nerves, chiasm and ipsilateral carotid artery, making the presellar

anatomy easily understandable. On the other hand, it does not give

good access to the area beneath the ipsilateral optic nerve and tract,

and the region of the third ventricle.

c) The transcallosal

approach uses a fronto-parasagittal craniotomy. This route is

preferable when the tumor is within or in the region of the third

ventricle and the tumor pushes the anterior hypothalamus forwards.

In these situations a basal approach would result in damage to the

hypothalamus before the tumor has been reached. This approach offers good

visualization of both walls of the third ventricle. Anterior corpus

callosum needs to be divided and there is a risk of bilateral fornix

damage.

d) The transcortico-ventricular

approach is associated with a cortical incision, requires the

presence of hydrocephalus, and allows limited visualization within the

third ventricle. This offers good visualization of the ipsilateral

foramen of Monro.This technique has been largely abandoned.

e)

Transsphenoidal surgery avoids craniotomy and is best reserved for

patients with enlarged sella and intrasellar infradiaphragmatic,

primarily cystic craniopharyngiomas. Enlargement of the sella is of

primary importance when using this approach, since it implies that the

tumor took origin under the diaphragma sellae, thus it is not attached to

the suprasellar structures such as the chiasm or hypothalamus, making

total removal possible. This approach is also used to drain cystic

tumors, and as part of staged surgery in partially intrasellar tumors.

Tumor dissection

uses combinations of routes.

The interoptical

route, between the optic nerves, gives an excellent view of both carotid

arteries. The optic carotid pathway lies between the carotid artery

and the optic nerve and tract.

Intraventricular

craniopharyngiomas can be approached through the lamina terminalis.

This pathway permits visualization of the anterior third ventricle and

gives access to supra- and retrochiasmatic masses, but carries the

highest risk of hypothalamic damage..

The lateral and

clival tumor surface can be approached between the carotid

artery and oculomotor nerve.

The intracranial

transsphenoidal pathway requires drilling partially away the

tuberculum sellae and the anterior wall of the sellae and opening the

sphenoid sinus without disrupting its mucosal membrane. This can be

useful when the tumor has a deep intrasellar extension, and when the

chiasm is prefixed.

In cases of

hydrocephalus, primary tumor removal usually re-establishes normal CSF

pathways avoiding shunting. However, when the hydrocephalus is

pronounced ventricular shunting may be performed as a first step.

The surgeon

should be familiar with these approaches and should use a combination of

these techniques as necessary.

Surgical technique:

Once all the major neural

and vascular structures are identified, each of the possible routes of

approach is evaluated and the greatest possible tumor surface is exposed.

Since these are subarachnoid tumors, the preservation of the plane

between the tumor capsule and the arachnoid is essential for safe and

total tumor removal. Besides general brain protection, the entire

intradural area is lined with cotonoids to prevent the spread of the

irritating crystalline content of cyst or solid tumor on to the brain or

into the CSF, as it may lead to an aseptic meningitis or hydrocephalus

postoperatively.

The optic nerves and chiasm

are most often found to be stretched anterosuperiorly by the pressure of

the tumor. After additional manipulation, any residual function may be

lost. Upwards displacement of the optic nerves against the sharp upper

edge of the optic foramen invariably results in visual loss. Before

causing more damage to the optic nerve, the foramen should be

decompressed at an early stage by partly removing its bony roof and

opening its dural sleeve.

The usually severely

compressed pituitary stalk and infundibulum may be found displaced

behind, above or lateral to the tumor. Preservation of the stalk, in

cases when it is not destroyed by the tumor, may occasionally be

possible. Although it may be functionally disconnected by the tumor

compression and surgical manipulation, a remnant of stalk reaching from

the medial eminence to the pituitary gland may serve as a matrix upon

which the pituitary portal system may reform.

Aspiration of any cyst is

the first step. The arachnoid covering of the tumor is carefully opened.

Entering the tumor with a microsuction tip will further decompress the

tumor. As the tumor mass decreases, more of the arachnoid capsule may be

exposed by dissecting in the plane around the tumor. Craniopharyngiomas

tend to get their arterial blood supply from the vessels of the anterior

circle of Willis. Direct branches from the carotid, the anterior cerebral

and the posterior communicating arteries have been described. Within the

sella turcica the tumor may be supplied by small perforating branches

directly from the cavernous portion of the internal carotid artery. They

do not receive blood from the posterior cerebral or basilar arteries

unless the third ventricle is invaded. These feeders may be coagulated

and divided. The interior of the tumor is entered and the solid portion

removed piecemeal. As the tumor is progressively gutted, the capsule may

be gradually resected.

Every effort should be made

to preserve the arachnoid capsule so that leaving behind torn-off bits of

the capsule is avoided. Even the tiniest scrap left behind can cause

tumor recurrence. Using small angled dental mirrors is recommended to

gain vision to the undersurface of the optic apparatus and hypothalamus.

Use of endoscope is a better option.

Tenacious adhesions of tumor

to main and perforating arteries, usually on the anterior circle of

Willis, are the most common obstacle to achieving total removal. This

mesenchymal reaction to the craniopharyngioma capsule appears to be

denser than the glial scar that forms underneath the chiasm or

hypothalamus.

Intraoperative arterial

damage should be avoided during dissection of these adherent parts.

Large solid calcified

portions can be difficult to break up and remove as they may pose a risk

to the neural and vascular structures as the jagged pieces of calcified

material are delivered past them. Calcified tumors, particularly those

adherent to or enclosing vital structures, have a lesser chance of total

removal.

In tumors that infiltrate

the hypothalamus it may be found that in some cases these structures can

be easily preserved, while in others it is impossible to distinguish

between the normal hypothalamus, the gliotic tissue and the tumor. The

ease of removal and risk of dissection can vary accordingly. A dense,

invasive finger-like tumorous and gliotic tissue with diffuse adhesions

of the hypothalamus renders it impossible to follow a plane of cleavage.

This situation limits the total respectability of these tumors.

Operative

complications:

a) Preoperative endocrine

deficiencies are irreversible in most cases. Surgical intervention,

however, often leads to additional endocrine disorders. After

craniopharyngioma surgery most patients have temporary or permanent

disruption of neurohypophyseal axis function even if function was normal

preoperatively. Among the various endocrine abnormalities, the loss of

ADH and ACTH will be the most important in the postoperative period.

Diabetes insipidus monitoring and therapy, and prophylactic treatment

with corticosteroid are essential. Long term endocrine follow-up with

appropriate replacement therapy is required with special attention in

children.

b) Surgical manipulation of

these tumors may result in hypothalamic dysfunction. Damage to the

hypothalamic nuclei and varying range of deficits such as sudden death,

alterations of consciousness ranging from somnolence to coma, water and

electrolyte imbalance, loss of thirst, hyper-, hypo-,or poikilothermia,

cardiac disturbances, hyperphagia, obesity, insomnia, hypogonadism,

growth failure.

c) Disturbance of

hypothalamic connections to the thalamus, limbic system, frontal lobes

and other cortical areas may explain some of the psychiatric and social

problems seen following treatment of cranipharyngiomas. Injury in this

area, from surgical or less frequently from irradiation treatment, will

result in problems common among these patients: confusion, short term

memory loss, mutism, emotional and sexual immaturity, psychic imbalance,

hyperphagia and aggressiveness.

d) Visual impairment is a

relatively common surgical complication but can be minimized with

technique. Direct surgical manipulation of the stretched optic nerve,

chiasm and tract or their vascular supply may result in additional visual

loss. Its reported incidence ranges from 1 to 17%. The degree of

preoperative visual loss and its duration (optic atrophy) are the most

important factors in determining postoperative visual status.

e) Three types of vascular

lesions have been described after craniopharyngioma removal. The first is

fusiform dilatation of the internal carotid artery which may develop due

to the weakness of the arterial wall following dissection of the adherent

tumor from the adventitia, or due to the injury of the vasa vasorum.

Secondly ischemic symptoms may develop at sites distant from the

operative field which is thought to result from the development of

vasospasm related to the operative manipulation to the vessels, to the

blood appearing in the subarachnoid space or possibly to some chemical

substances of the spilled cyst fluid. Finally, in cases of massive

hydrocephalus, intraoperative ventriculostomy can cause sudden collapse

of the cortex with subsequent stretching of the cortical and bridging

veins and multiple venous infarcts over the surface of the cortex.

f) CSF rhinorrhoea and

meningitis are the most common complications of the transsphernoidal

approach.

g) Other possible

postoperative complications such as cranial nerve palsies, epilepsy and

hemiparesis are related to the location and not the nature of this tumor.

Operative results:

At present, overall

mortality for total removal of craniopharyngiomas is under 10% in

experienced hands.

There is a strong

correlation between the size of the tumors and the outcome. Tumors

smaller than 4 cm are usually totally removed with good to excellent

results, while total removal of large (>4cm) tumor is associated with

significantly higher morbidity and mortality. These facts stress the

importance of early diagnosis and treatment of craniopharynigomas.

Virtually every series of

craniopharyngiomas has reported recurrences of tumor even after a

macroscopic total removal. Although these tumors are known as slow

growing tumors, they tend to recur early because of the capacity for

rapid growth of the cystic portions.

In different series, the

majority of recurrence was noted within 2 years of surgery, though

recurrences have been reported as late as 30 years after operation. In

one study, 52.5% recurred within one year, 75% within 3 years and 85%

within 5 years.

Reoperation and/or adjuvant

irradiation are recommended in cases of symptomatic recurrences. Surgery

of recurrent craniopharyngiomas has worse outcome in all series. The reported

mortality rates are much higher, being between 12 and 38% (Samii, 1995).

Recurrent tumors are more tightly adherent to vascular and neural

structures, making total excision more dangerous and therefore

impractical in many cases.

Yasargil

(144 cases, 1990) achieved total primary removal of craniopharyngiomas in

90%. Primary radical excision without additional radiotherapy was

associated with a good outcome in 76.8%, morbidity of 13.4% and an

overall mortality rate of 9.8%. The recurrence rate was zero in the

squamous papillary tumor group, 11% in the adamantinous group with a mean

follow up period of 7.5 years. The squamous papillary tumors were more

benign with a good outcome in 84.6%, and poor in 15.4%, without

mortality. Adamantous tumors fared worse with a good outcome in 51.6% in

adults and 73.9 % in children, mortality of 16.2% in adults and 6.5% in

children. In Hoffman’s review (1992) of 50 pediatric cases,

radical excision was possible in 90%, with a mortality rate of 6%. The

recurrence rate among these children was 34% with a mean follow up period

of five years. Symon (1991) reported 50 mostly adult cases of

totally removed craniopharyngiomas with a mortality rate of 4% and major

morbidity rate of 15%. The recurrence rate in his series was 6% within

the mean follow up period of 30 months.

These authors and their

results suggest that an attempt at total removal imposes no greater

burden upon these patients as a result of neural or endocrine damage than

other therapeutic modes would do.

Subtotal removal with

radiotherapy:

Most widely practiced.

When the goal of total

surgical removal is not reached, radiation therapy has the power both to

improve the survival and to prolong the interval preceding recurrence.

Radiation seems to be the best method of gaining control of tumor left in

situ.

Proponents of primary

subtotal or partial removal of craniopharyngiomas with radiation therapy

believe that their results are superior in outcome to those of radical

surgery with significantly less morbidity and mortality.

On the other hand, radiation

therapy just retards the regrowth of craniopharyngiomas, but is rarely

curative, and can lead to further endocrinological visual and

psychosocial compromise, especially to the immature brain. It does not

reverse most of the pre-treatment deficiencies, and carries the risk of

development of radiation-induced necrosis and neoplasms such as gliomas

and sarcomas.

Radiation-related morbidity

correlates strongly with the given radiation dose. In Regine’s

report (1993), 44% of all patients receiving tumor doses of < 54 Gy

developed recurrence after this treatment, while only 16% of those

receiving more than 54 Gy. However, any possible benefit in tumor control

with doses above 60 Gy at 1.8Gy per fraction appears to be offset by the

increased risk of radiation injury.

Those patients in whom

removal is deemed to be total should not be irradiated. Because of the

long-term effects of radiotherapy, some workers do not administer it

unless there is a symptomatic recurrence. Because the risk of further

endocrine and psychological injury by irradiation is related to the age

of the patient, it may be advisable to delay radiation therapy in

children for as long as possible.

In Wens’ series

(1992) of 34 cases, total excision resulted in 20% recurrence rate,

subtotal removal in 60%, and subtotal resection with radiation in 12.5%

recurrence rate within a mean follow up of 6.4 years. Wen concludes that

subtotal removal with radiotherapy is a significantly better mode of

treatment.

In Fischer’s series

(1990), management of childhood craniopharyngiomas was weighed toward

subtotal operations with irradiation. His series mortality of 8% and the

recurrence rate of 14%, as well as the social quality of life, are

comparable to or even better than the results of the more radically

oriented series.

Carmel

reported (1982) the 10 year survival rate to be 52% with subtotal removal

alone and 87% with subtotal surgery plus irradiation. Tumors recurred

within 10 years in 50% of those presumed to have had total removal, in

more than 90% of those subtotally removed and in less than 25% of those

after subtotal removal and irradiation.

Unfortunately there have

been no prospective studies comparing the efficacy of various treatment

modalities in craniopharyngioma.

Other modalities:

Instillation of

radioactive substances into the cyst isotopes such

as yttrium-90 or phosphorus-32 into craniopharyngioma cysts using

sterotaxy can successfully improve the clinical condition and survival.

About 60% of craniopharyngiomas are mainly cystic, and this rate is

higher in cases of recurrence. Injections of colloidal these implanted

isotopes directly destroy the epithelial lining of the cysts, and cause

accumulation of collagen fibres, hyaline degeneration and vascular occlusion,

thus indirectly damaging the secreting tumor cells. Follow up diagnostic

studies show gradual cyst regression, which commences a few months after

installation, with cyst obliteration in 75% of the cases. A precise

knowledge of the cyst volume is necessary to determine the amount and

dosage of radioactive isotope to be injected. The optimum dosage of

radionuclide should be sufficient to destroy cyst epithelium while

minimizing damage to surrounding structures.

Intracavitary brachytherapy

can be combined with external fractionated radiation therapy to address

the solid components of the tumor not treated by the beta-radiation

emitter. Like surgery, visual improvement is likely in patients with

moderate deficit, but is less evident in patients with severe visual

loss, while endocrine deficiencies seldom change.

Cyst drainage

(Percautaneous) drainage of a unilocular cyst by means of a

sterotactically implanted catheter, linked to a subgaleal reservoir

allows periodic aspiration of the cyst fluid. This technique also allows

the placement of radioactive or chemotherapeutic substances into the

cystic tumor in temporary or permanently inoperable cases this modality

seems to offer a safe alternative.

Radiosurgery

should be considered in cases when the solid component of primary or

residual tumor is smaller than 2.5 cm in the longest diameter. It is a

primary treatment alternative for elderly or medically infirm patients,

or for those who refuse surgery. Further follow-up is necessary to

evaluate the long-term tumor control rate and the tolerance of

surrounding critical structures.

Chemotherapy: Intracavitary

installation of bleomycin and methotrexate has been reported with

promising results. These agents might work by decreasing the secretion of

cystic fluid and causing tumor cell degeneration. Systemic chemotherapy

of craniopharyngiomas has been used sporadically in patients who refused

other methods, with some merit.

These results warrant

further evaluation of the effect of chemotherapy on craniopharyngiomas.

|