|

Dermoids and

epidermoids are the result from an abnormality of surface ectoderm, and

invariably associated with one or more mesodermal malformations, such as,

those involving the vertebrae.

Similarly,

neuroenteric cysts are due to an endodermal malformation.

Other developmental cysts, including the Arachnoid cysts

are discussed elsewhere.

EPIDERMOIDS:

Epidermoid cysts constitute

approximately 0.2 to 1.8% of all intracranial tumors and less than 1% of

all intraspinal tumors. Cranial sites outweigh spinal sites by 14:1.

Although these lesions are congenital, patients are usually not

symptomatic until they are aged 20-40 years.

Pathology:

They are benign

congenital lesions of ectodermal origin. Epidermoid cysts represent nests

of cutaneous tissues misplaced during embryogenesis and found along lines

of ontogenic neurocutaneous differentiation. These ectodermal inclusions

occur between 3rd & 5th Weeks of

embryonic life. This inclusion can result in heterotopia of these

elements. The median location of these tumors can be explained by the

separation of neuroectoderm & its cutaneous counterpart which occurs

dorsally along the midline. Laterally situated lesions may result from

inclusion of ectoderm at a later stage of embryogenesis, especially

during the formation of secondary otic and optic cerebral vesicles.

In

the

spine these lesions are usually associated with spinal dysraphism

. Acquired epidermoid cysts in the lumbar area are due to repeated lumbar

punctures or incidental formation of a skin pocket by suturing.

Grossly, they are well

circumscribed, smooth or lobulated, encapsulated friable lesions with a characteristic glistening pearl like

sheen. Typically, the epidermoid contains white, flaky, kertinous debris.

|

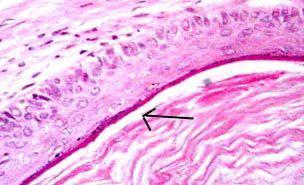

Histologically, they appear

as an internal layer of keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium

with a whitish fibrous capsule; these features account for the term

pearly tumor. They tend to slowly enlarge as epithelial cells

desquamate, with the formation of keratin and cholesterol crystals in

the center of the lesion.

Approximately, 25% are situated intradiploically

in the skull or spine. The vast majority of epidermoids are intradural

The most common locations are within the cerebellopontine (CP) angle,

parasellar region,pineal region and middle cranial fossa.

|

|

|

|

Epidermoid

cyst (H&E): The cyst is lined by epidermal layer(arrow)

(keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium).

|

|

The

CP angle is the most common site for epidermoids. Of all CP angle masses,

epidermoids are the third most common after vestibular schwannomas and

meningiomas. Occurrences within the ventricular system, brain parenchyma,

and even the spinal cord, have been reported.

At

diagnosis, epidermoids usually insinuate within the sulci and cisterns,

and they may engulf cranial nerves and blood vessels.

Clinical

features:

Clinical

features depend on the site of location, and indistinguishable from any

other mass lesion. The average age of presentation is 35 years with a

female predominance. They grow linearly, similar to normal skin, and thus

have an insidious onset. Rarely, there may be features of aseptic

meningitis, caused by leakage of the debris into the subarachnoid spaces.

Spinal

epidermoids are usually associated with vertebral anomalies.

|

Imaging:

Skull

radiographs

may reveal a lytic lesions with well-defined sclerotic borders. Rarely

the epidermoids show calcifications.

CT

and MRI

are both helpful in diagnosing epidermoids. Although CT findings may be

nonspecific, MRI findings are reliable in diagnosis.

|

|

|

|

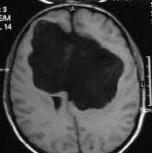

Bifalx epidermoid- MRI

|

|

Epidermoids

lesions usually have the same attenuation as that of cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF); this characteristic makes their differentiation from arachnoid

cysts difficult; however, the margins of these lesions are typically

lobulated and may contain fine linear strands. They may also envelope

rather than displace surrounding structures such as cranial nerves. Enhancement

is rare, but can sometimes be seen around the margin of the tumor.

Differentiation from CSF filled

lesions can be made on diffusion weighted MRI because these lesions have

diffusion characteristics of solid tissue whereas the diffusion

characteristics of an arachnoid cyst are similar to CSF. These lesions

also show significant magnetization transfer on magnetization transfer

sequences whereas arachnoid cysts show no magnetization transfer.

The contents of the cyst may also

rarely demonstrate high signal on T1-weighted sequences similar to a

lipoma or dermoid. Because the latter two lesions contain fat chemical

shift artefact will be present whereas an epidermoid contains no fat.

This distinction can also be made by applying a fat saturation sequence

which will leave an epidermoid unchanged whereas the high signal from fat

will disappear if the lesion is a dermoid or lipoma.

Proton

density–weighted and then fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)

images were first used to differentiate epidermoids from arachnoid cysts.

These sequences demonstrate epidermoids as being hyperintense relative to

CSF.

Now,

diffusion-weighted imaging can be used to differentiate these entities,

because epidermoids have markedly restricted diffusion and, therefore,

high signal intensity on the diffusion-weighted trace images. The free

water in arachnoid cysts has low signal intensity.

Diffusion-weighted

images are helpful in assessing residual epidermoid tumors after surgical

resection.

Contrast

enhancement suggest a malignant epithelial component.

Management:

Treatment

is surgical removal. Asymptomatic, incidentally discovered cysts need not

be removed, but followed up regularly. Gross total resection is the goal,

but because the cysts can be very adherent to adjacent blood vessels,

total excision is not always possible. The capsule is the living portion

of the tumor, and viable portions that remain will likely regrow, but at

such a slow rate that the tumor may not become symptomatic during the

patient's life time. Spillage of the contents must be prevented, as they

may cause severe chemical meningitis.

There

is no role for radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

The

tumor marker CA 19-9 is positive in many cases and may provide a means of

follow up for the residual and recurrence.

DERMOIDS:

They

are also been described as hamartomas, hamartomatous tumor, dermoid

cystic tumor, cystic teratoma, congenital cyst of the spine, spinal

dermoid cysts, subcutaneous cysts.

Dermoid cysts can be

intracranial, intraspinal, or perispinal.

Pathology:

|

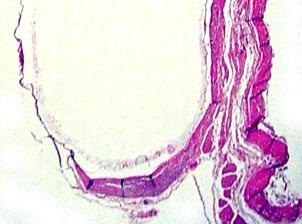

Dermoid cysts are true

hamartomas. Dermoid cysts are a result of

the sequestration of the skin

along the lines of embryonic closure.

They are benign and demonstrate

both dermal and epidermal elements.

The tumor is covered by a thick

dermis like wall that contains

multiple sebaceous glands and

almost all skin adnexa. The dermoid

contents

include cheesy, granular material. Hairs and large amounts of

fatty masses cover poorly to

fully differentiated structures derived

from the ectoderm. The dermoid cyst also contains

pilosebaceous

units with

hair shafts and sebaceous glands. Dermal elements may

be found

in only a small part of the capsule, and the rest of the cyst

wall may

closely resemble an epidermoid cyst.

A dermal

sinus tract may connect the cyst to the skin surface,

especially

when the cyst is located in the posterior fossa,

or spinal

canal.

|

|

|

|

Dermoid cyst (H&E): The cyst

shows both epidermal and dermal (adnexal structures-arrow)

lining.

|

|

Clinical features:

Symptoms depend on the location

and are, usually, that of any other mass lesion.

They are more commonly seen in

the spine than the brain.

When found in the brain, they

tend to be in the midline.

Dermoid cysts are usually seen in

children, unlike the epidermoids which are seen in adults and can

be associated with episodes of aseptic meningitis, due to leakage

of its content.

|

In

some patients, spinal dermoid cysts, especially those connected to

dermal sinus tract, lead to severe neurologic complications such as

secondary spinal subdural abscesses caused by the spread of the

infection in the dermoid cyst.

Imaging:

CT

and MRI

are helpful in making the correct differential diagnosis of dermoid

cysts. 20% of the dermoids calcify.

MRI

is particularly helpful in diagnosing intracranial or intramedullary

dermoid cysts and in assessing the dissemination of fatty masses or

droplets and also the associated sinus tracts. MRI is helpful in

planning surgical procedures and in assessing therapeutic success. They

are usually hyper dense on both T1 and T2, and more solid than

epidermoids, they are less likely to insinuate between neurovascular

structures and tend to demonstrate more of a local mass effect with no

edema.

Management:

|

|

|

|

Spinal dermoid-MRI

|

|

Surgical

excision is the treatment of choice in any localization, and the excision

is easier than in an epidermoid. Several possible complications of

spontaneous or posttraumatic rupture and surgical procedures have been

described. In patients with a ruptured spinal dermoid cyst, fatty

droplets can disseminate in the cerebrospinal fluid or in a dilated

central canal of the spinal cord. In other patients, subarachnoid

and ventricular fat dissemination can occur after the cerebellopontine

angle dermoid cyst is resected. Spinal subdural abscesses are a

possible complication because of the bacterial infection of spinal

dermoid cysts in a dermal sinus tract.

As

in epidermoids, the tumor marker CA 19-9 is positive in many cases and

may provide a means of follow up for the residual and recurrence.

NEUROENTERIC CYSTS:

(also known as enterogenous cysts,

endodermal cysts, archenteric cysts, gastrocystomas, intestinomas, cystic

teratomas, foregut cysts)

They represent approximately 0.7% of

tumors and 16% of cysts in the CNS. 5% of patients with Klippel-Feil

syndrome and vertebral fusion abnormalities may have enteric cysts.

During normal development, the

neuroenteric canal closes and the notochord separates from the primitive

gut in the third week of embryonic life. It is proposed that during the

same period, a transient adhesion occurs between the neural ectoderm and

endoderm, or a communication develops along the neuroenteric canal.

When such a developmental abnormality persists because of the

incomplete separation at this adherence or remnant canal, the cyst

forms. They are often associated with developmental defects of the

overlying skin and/or vertebral bodies.

Enterogenous cysts of the central

nervous system occur most frequently in the spinal canal, especially in

the lower cervical and upper thoracic(42%) regions with intradural,

extramedullary location. Intracranial neurenteric cysts are typically

intradural, extra-axial posterior fossa masses.

|

They are benign epithelial

lined cysts, with the lining resembling that of the alimentary canal.

They are well delineated, thin walled, fluid containing masses. These cysts are similar to

Rathke cleft cysts and colloid cysts at histologic and immunochemical analysis. The location of

these lesions on images is an important distinguishing feature. A Rathke cleft cyst is usually sellar or

suprasellar, whereas a colloid cyst is related to the anterior wall of the

third ventricle adjacent to foramen of Monro. Neurenteric cysts have been reported in the

cervical, thoracic, and lumbar portions of the spinal canal, the posterior cranial fossa, the suprasellar

cistern and the

anterior cranial fossa.

The cyst wall is composed of

fibrous connective tissue with an underlying epithelium that resembles

gastrointestinal or respiratory tract mucosa (unlike the arachnoid cyst

which is lined with meningothelial cells).

Cyst contents vary from

colorless, transparent fluid resembling CSF to milky or mucinous like

secretions. Occasionally they can have fistulous connection with

similar mediastinal, thoracic or abdominal cysts, thus supporting an

endodermal origin of these cysts.

|

|

|

|

Enteric

cyst (H&E): Cyst lined by simple columnar and cuboidal

epithelium.

|

|

|

Their intracranial occurrence

and the lumbar spine are rare sites.

Between 85% and 90% are

midline; most are located ventral to the spinal cord or brain stem.

Spinal variety is more common in men, whereas the intracranial ones are

commoner in women. They may be asymptomatic lesions that are

discovered incidentally; the larger ones present with gross

ataxia, nystagmus, visual symptoms and cranial nerve palsies.

Pain and myelopathic symptoms are common in spinal lesions;

septic or chemical meningitis may occur. They may present prenatally up

through adulthood. In adults the presentation is slow and insidious.;

progession is rapid in children.

CT scan reveals a well

delineated, non enhancing, noncalcified lobulated mass that is

typically hypodense compared to adjacent brain parenchyma. It may be

difficult to defferentiate from arachnoid cyst on CT.

MRI signal varies with cyst

content; most lesions are iso to mildly hyperintense compared

to CSF on T1-weighted images

and moderately hyperintense on proton density and T2-weighted

sequences. Spinal ones are, invariably associated with vertebral

anomalies.

Differential diagnosis includes

arachnoid and neuroepithelial cysts, epidermoid cyst, cystic schwannoma

and inflammatory cysts such as cysticercosis.

|

|

|

|

Cervical neuroenteric cyst-MRI

|

|

Treatment is surgical

excision. The goal is complete excision, which is not always possible.

Simple aspiration, cyst wall

marsupialization, or cysto-subarchnoid shunt may be employed when total

removal is not possible. There is no role for radiotherapy or

chemotherapy.

|