|

These rare but interesting lesions

comprise 1 per cent of all brain 'tumors'. The spectrum of developmental

cysts in CNS include, arachnoid cysts, ependymal cysts, colloid cysts,

dermoid and epidermoid cysts, Dandy walker cysts ,epithelial cysts, and

porencephalic cysts. They are mostly intracranial, but can occur

intraspinally as well.

1) ARACHNOID CYSTS

(leptomeningeal cysts):

They were referred by Richard Bright in

1831 as ‘serous cysts of the arachnoid’; he described cystic lesions with

liquid, clear, contents and intra-arachnoidal localization. About

127 years later, Starkman described the intra-arachnoid localization of

these cysts, giving an explanation for their etiology.

Epidemiology:

Arachnoid cysts correspond to about 1%

of all intracranial lesions in the general population and about 3% in the

pediatric population. Although 60-90% of reported cases have been

found in young people (less than 20 yeas old), it is possible to find

them in the elderly.

The sex distribution shows a preference

for the males, in the ratio of 3:1 and for left side of the CNS

structures.

Etiology:

They are congenital lesions that

probably arise during development from splitting or duplication of this

membrane.

The etiology of these lesions is

extremely controversial.

Intra-arachnoid cyst theory theory

suggests a congenital origin for the etiology of the arachnoid cysts; at

some time during development, there is a duplication of the arachnoid

membrane, proliferation of the arachnoid cells, forming a cavity which

later fills with CSF through several mechanisms. This was defended

by Starkman and suggested by Bright in 1831. Frequently these cysts are

associated with venous anomalies and the developmental anomaly probably

occurs between the sixth and eighth week of fetal life, precisely when

the vascular structures begin their development.

Shreiber, suggested that most arachnoid

cysts were caused by incomplete canalization of the subarachnoid space

with the formation or pouch like spaces which become distended with CSF

consequent upon arterial pulsation.

Dott and Gillingham, also postulated

that such pouches usually form along the axis of a main cerebral artery,

that the leptomeningeal space at the distal boundary of a cistern becomes

occluded and that the fluid propelled into the proximal portion cannot

escape over the convexity of the brain.

The striking and nearly invariable

association of arachnoid cysts with normal subarachnoid cisterns has led

to hypothesize that arachnoid cysts represent a congenital anomaly

of the developing subarachnoid cisterns in early intrauterine life. It is

postulated that, during the process of the complex folding of the

primitive neural tube and the formation of normal subarachnoid cisterns,

an anomalous splitting of the arachnoid membrane occurs.

Cysts of the sellar region (supra, para

and intrasellar) are considered to be an extension of the Lillequist

membrane, which divides the chiasmatic cistern of the interpeduncular

cistern, being associated with alterations of the normal CSF flow.

Cysts of the posterior fossa are

probably caused by various degrees of obstruction of the foramens of

Luschka or Magendie. Intraventricular cysts are explained by

mesenchymatous invagination through the choroidal tissue that is formed

by digitations of pia-mater with arachnoidal stroma.

Spinal intradural cysts are related to

the septum posticum at a thoracic level, and thoracolumbar extradural

cysts are explained as invaginations of the arachnoid through small

pre-existent dural defects.

The fact that the arachnoid cysts occur

mainly in young people (less than 20 years old) with a strong incidence

in the first years of life as well as the occurrence of case reports with

a familiar incidence and the frequent association of these cysts with

diseases related to chromosome alterations (polycystic kidney,

neurofibromatosis, chromosome 12 trisomy) reinforce the possibility of a

congenital origin for these lesions.

Apart from the structural alterations

there is an alteration of the normal CSF flow, as confirmed in some

cases, by the persistence of symptoms in patients whose cysts were

surgically removed.

Pathology:

|

An arachnoid cyst is by

definition, a benign lesion, with well defined outlines, within the

arachnoid membrane or covered by layers of arachnoid cells supported by

collagen fibres, having liquid contents similar to CSF. It is a

cavity, whose walls are formed by arachnoid cells (simple or multiple

layers), supported by a stroma, rich in collagen fibres.

They can develop anywhere along

the cerebro-spinal axis, but almost all occur in relation to an

arachnoid cistern.

The distribution of arachnoid

cysts in two hundred and eight reported cases is as follows:

Sylvian fissure, 49%;

cerebellopontine angle, 11%; supracollicular area, 10%; the vermis, 9%;

sellar and suprasellar area, 9%; interhemispheric fissure, 5%; cerebral

convexity, 4%; and the clival and interpeduncular area, 3%.

|

|

|

|

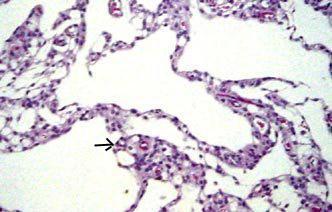

Lobulated

arch.cyst(H&E)- lining of meningothelial (arrow)

cells supported

by collagen fibres.

|

|

A lesser percentage occurs within the ventricular

system. Intrasellar cysts are the only intracranial arachnoid cysts that

are extradural. Intraspinal cysts are rarer.

The structural features of the arachnoid

cyst wall that distinguish it from the normal arachnoid membrane are

(1) splitting of the arachnoid membrane at the margin of the cyst,

(2) a very thick layer of collagen in the cyst wall,

(3) the absence of traversing trabecular processes within the cyst, and

(4) the presence of hyperplastic arachnoid cells in the cyst wall, which

presumably participate in collagen synthesis.

Most of the small arachnoid cysts do not

increase in size and can be asymptomatic, but the larger cysts can become

bigger and produce symptoms.

The possible reasons for the increase in

size:

The active secretion through the cyst

wall inside the cavity

Unidirectional valve mechanism (ball

valve) with CSF flow from the sub-arachnoid space into the cyst

The active osmosis through the wall by a

similar mechanism to that which occurs at the Pacchionian granulations

Pulsations of the CSF and of the

intracranial arteries transmitted to the cyst cavity through a wide

opening into the sub-arachnoid space.

Transudation through the wall cyst from

the choroids plexus (in the intraventricular cysts).

It is not known which mechanism is

responsible for the increase of the cyst volume, which is probably

multifactorial. However in intraventricular cysts related to the

choroid plexus, the principal mechanism is the transudation through the

cyst wall from plexus secretion. For cysts that are in

communication with the sub-arachnoid space, the principal mechanism is

likely to be the ‘bell valve’ effect and in non-communicating cysts,

active secretion mechanism or osmosis may be more likely.

A classification based on cisternography

with metrizamide and CT isotopic cisternography and, more recently cine

MRI, defines the existence of communication with the subarachnoid space

and the cavity of the cyst. The cyst can then be as slowly or rapidly

communicating or non communicating (real cysts).

A classification based on etiology

divides the cysts into primary (congenital) or secondary (traumatic or

infectious origin).

Finally a classification which is based

on the morphology, volume and effect on the CNS structures and bone

structure as suggested by Galassi divides the cysts into 3

types. Type 1 are small asymptomatic cysts, type II have some mass

effect, with bone erosion and type III have deformation of large areas of

the CNS and gross bony changes.

Clinical features:

In many instances, an arachnoid cyst is

an incidental finding. The clinical presentation will depend on the

location and size of the

achnoid cyst, and the symptoms often are

mild considering the large size of some cysts. Most patients will come to

medical attention in the first two decades of life, often in the first 6

months.

These lesions cause symptoms and signs

of increased ICP by compressing the normal tissue and obstructing the CSF

pathway.

The symptoms depend on the cyst

localization. Symptoms and signs include cranial enlargement, localized

cranial bulging, especially the large cysts, can present acutely with

sudden deterioration.

Suprasellar cysts may also present with

endocrine symptoms, head bobbing, and visual disturbances. Either

communicating or obstructive hydrocephalus is often present. In the

elderly, dementia has been described.

Intraspinal cysts may produce a tetra or

para paresis, with abnormal reflexes, sphincter dysfunction, sensibility

alterations and radicular pain according to the level of the lesion.

Investigations:

Arachnoid cysts are usually diagnosed by

CT or MRI. Further evaluation with CSF contrast flow studies is only

occasionally necessary for the diagnosis of midline suprasellar and

posterior fossa lesions.

CT shows a smoothly bordered

noncalcified extraparenchymal cystic mass with density similar to CSF and

no contrast enhancement and also the bony remodeling.

MRI may show the arachnoid membrane and

also differentiates the CSF in the arachnoid cysts from the neoplastic

cysts and ependymal ( usually, intraparenchymal) cysts. Porencephalic

cyst usually communicate into the ventricle. In addition associated

cerebral and cerebellar hypoplasias are well studied.

Deep invagination of an arachnoid cyst

into the cerebral hemisphere may simulate porencephaly to such an extent

that it has been termed pseudoporencephaly. However, the inferior aspect

of the arachnoid cyst shows a displaced but otherwise normal cerebral

cortex, while in porencephaly, the surrounding cortex and white matter

are abnormal.

Management:

The cysts, that do not cause mass effect

and have not changed in size need not be treated.

Many procedures for treatment of

arachnoid cysts have been proposed. Surgical options for arachnoid cysts

include drainage by needle aspiration, craniotomv with excision of the

wall and fenestration into the basal cisterns (open or endoscopically)

with or without a silastic shunt, and shunting of the cyst into the peritoneum

or vascular system.

The Fenestration and shunting are the

two most common options.

Shunting of the cyst material into the

peritoneum or into the vascular system is associated with low morbidity

and mortality and a relatively low rate of recurrence, but the patient

becomes shunt dependant. Long-term complications of a shunt occur in

more than one third of cases. Low pressure shunt is preferred.

Craniotomy with excision of the cyst

wall and fenestration into the basal cisterns permits direct inspection

of the cyst and avoids placement of a permanent shunt in some cases.

However, it is associated with reaccumulation of CSF at the cyst site. In

addition, significant morbidity and mortality may accompany; abrupt

displacement of brain structures following the rapid decompression that

accounts for the unexpected rapid deterioration.

Endoscopic approaches have been used

with good results, although the follow-up period has not been long. The

goal of fenestration is free communication with the basal cisterns.

Shunting the associated hydrocephalus

alone will only worsen the symptoms, and may increase the size of the

arachnoid cyst.

Outcome:

Arachnoid cysts are benign lesions, with

a poorly defined natural history, sometimes with spontaneous disappearance.

Regression of cyst volume post-surgery,

occurs independently of the surgical technique. Sometimes the cyst

volume remains constant, leaving the patient without symptoms.

Usually there is a good clinical and imaging correlation of regression.

For the suprasellar cysts with

hydrocephalus, it is common to have persistent ventricular dilatation in

spite of the cyst having decreased in its volume, with normal

intracranial pressure. This has no consequences in the intellectual

development of the patients. For the sellar cysts it is also common to

have persistence of endocrinological alterations, even with cyst

disappearance.

Arachnoid Cysts by location:

Sylvian fissure/Middle cranial

fossa cysts:

The sylvian fissure is the most common

site for arachnoid cysts (50% of adult cases and 30% of pediatric cases).

They are usually small or medium, but they can become quite large and

open up the fissure to expose the insula and middle cerebral branches.

They usually manifest clinically in children or adolescents, but can

present at any age. Males predominate and the left hemisphere is more

commonly involved.

Global headache, seldom severe, is

common. Macrocephaly or an asymmetric macrocrania is often the

presentation in the young.

Children may present with developmental delay. Acute symptoms of

increased ICP, hemiparesis, or seizures are common.

On CT and MRI, the large cysts extend

posteriorly and open up the sylvian fissure. The temporal lobe may be

underdeveloped. The greater wing of the sphenoid may be displaced

anteriorly and the lesser wing may be elevated. In most cases, the

associated hydrocephalus is due to compression of the 3rd ventricle.

Treatment is either shunting the cyst or

fenestration of the cyst into a cistern or both combined. Symptoms

typically improve after successful treatment. Results are poor when

behavioral abnormalities and mental retardation are present.

Suprasellar cysts:

Suprasellar location accounts for

approximately 10% of arachnoid cysts and less than 1% of intracranial

mass lesions. Cysts in the suprasellar region appear to arise from the

suprasellar cistern. It has been suggested that the cysts may arise from

an imperforate membrane of Lillequist.

Typically, most patients are adolescents,

and present with hydrocephalus. Adults present with visual problems.

Hypopituitarism, especially the growth hormone deficiency, can occur.

Rarely, there may be ‘bobble head-doll’

syndrome. They experience an involuntary two or three times per second

vertical bobbing of the head, with compensatory horizontal movements of

the trunk, attributed to the abnormal pressure exerted by the cyst on the

3rd ventricle and on the dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus.

On CT and MRI images, a suprasellar arachnoid

cyst appears as a smooth, oval or round lesion in the region of the third

ventricle .

Multiple approaches to suprasellar cyst

fenestration have been attempted, including transfrontal removal of the

anterior portion of the cyst, a transcallosal approach to communicate the

cavity of the cyst into the ventricular system, and insertion of

catheters between the cyst and ventricle or chiasmatic cisterns. Any one

of these operations has a poor chance of prolonged success and may fail

to decrease either the size of the cyst or the ventricular system.

Shunting the associated hydrocephalus

will only worsen the symptoms, and may increase the size of the arachnoid

cyst. A combination of cyst fenestration and ventricular shunting may be

more successful.

Convexity and Interhemispheric

fissure cysts:

Convexity lesions differ from arachnoid

cysts in other locations due to their lack of contact with cisternal

spaces. Determining the origin of interhmispheric cysts can be

difficult. Imaging of the corpus callosum, third ventricle, and

collicular plate is essential, because the third ventricle can herniate

into the interhemispheric fissure, mimicking an arachnoid cyst.

Usually, they are incidental findings.

Adults can present with raised ICP, epilepsy, and focal neurological

deficit. Children may present with localized macrocrania.

CTand MRI demonstrate rounded lesions

with CSF density, overlying the cerebral cortex or interhemisheric area.

Typically, they are treated with

cysto-peritoneal shunting, often with excision of the outer cyst wall.

Most of these cysts have been detected

in patients aged less than 15 years. Symptoms frequently arise from

hydrocephalus secondary to compression of the posterior third ventricle

or the aqueduct.

Quadrigeminal plate arachnoid

cysts:

Pupillary reactivity or eye movements

are disturbed due to compression of the quadrigeminal plate or stretching

of the 4th nerve.

|

CT and MRI show an ovoid

collection posterior to the 3rd ventricle.

Definitive surgical treatment

can be difficult because the region is not easily accessible.

Fenestration followed by shunting may have a better success. Recurrence

is high.

Intraventricular arachnoid

cysts:

The differential diagnosis

includes ependymal cyst, epidermoid cyst, dermoid cyst, infectious

cyst, and porencephalic cyst.

MRI is the definitive study.

Asymptomatic cavum septi pellucidi, and septum cavum veli

interpositi may be considered

normal variants.

|

|

|

|

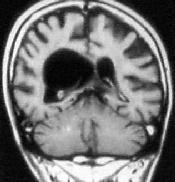

Intraventricular

arach.cyst

|

|

Simple drainage is usually followed by

reaccumulation. Endoscopic fenestration, craniotomy and cyst excision,

cyst-peritoneal shunting are the surgical options.

Posterior fossa archnoid cysts:

They are less common, about 25% of all

intracranial cysts and usually occur in the midline, superficial to the

vermis or in the CP angle. Less frequent locations include the cerebellar

convexities, or pre pontine areas. The posterior fossa is a common site

of benign intracranial cysts, especially in children.

The differential diagnosis of a

posterior fossa include, arachnoid cysts, Dandy-Walker

malformation, and mega cisterna magna.

|

|

|

|

|

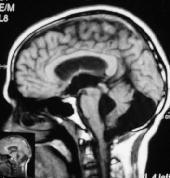

Post.

fossa arch. cyst- MRI

|

Dandy-walker

cyst-MRI

|

Mega

cisterna magna-MRI

|

|

An

arachnoid cyst results in anterior displacement of the fourth

ventricle, but normal cerebellar development.

|

Dandy-Walker

malformation is a cystic dilatation of the fourth ventricle or a cyst

in communication with 4th ventricle.

|

Mega

cisterna magna is an anatomic variant with normal fourth

ventricle and small cerebellum.

|

Most pediatric patients present with

macro crania. In adults, there are intermittent symptoms or influenced by

posture. CP angle lesions can cause tinnitus or hearing loss.

Fenestration, cyst shunting, and

combination of shunting and fenestration are the treatment options. A

ventricular shunting is often necessary, as the hydrocephalus often fails

to resolve with cyst decompression. Deeper cysts are often

multiloculated, and probably would not respond to shunting and are

usually treated with fenestration.

Spinal arachnoid cysts:

|

Arachnoid cysts also occur

within the spinal canal, in which arachnoid cysts or arachnoid

diverticula may be located subdurally or in the epidural space,

respectively. They are rarer than intracranial cysts. Extramedullary

location is common. They are mostly congenital in origin.

Typically,

spinal arachnoid cysts occur at the midthoracic level and, less

frequently, at the lumbosacral or sacral level. Commonly located dorsal

to the cord. A cyst in this location is usually secondary to a

congenital or acquired defect and is situated in an extradural

location. Intradural spinal arachnoid cysts are secondary to a

congenital deficiency within the arachnoid or are the result of

adhesions resulting from previous infection or trauma.

|

|

|

|

Intramedullary Spinal

Archnoid cyst

|

|

They cause symptoms indistinguishable

from cord compression due to other causes. Patients with spinal arachnoid

cysts may become symptomatic as a result of local cord displacement or

cord compression. Epidural arachnoid cysts often are associated with

kyphoscoliosis in juveniles. Arachnoid cysts also are associated with

myelodysplasia in spinal dysraphic lesions. Pain produced by intraspinal

arachnoid cysts typically is aggravated by the Valsalva maneuver, which

increases pressure within the cyst.

Remission of symptoms is not uncommon.

Surgical excision is curative.

Tarlov cysts (Spinal perineurial

cyst):

Many consider this a degenerative cyst

and not developmental.

Tarlov described this cyst in 1938,

while conducting an anatomic study of the filum terminale. It is a cystic

dilatation of the subarachnoid space around a nerve root (between

the perineurium of the nerve root and the outer surface of its pia). The

cyst can dissect into the nerve and can contain nerve fibers within

it. These cysts typically involve the sacral nerve roots. It is

found on as many as 5% of lumbosacral MRI.

It is usually

diagnosed incidentally. Approximately, 4 out of 5, are asymptomatic.

Some may present with radicular pain, frequently

occurring in attacks with pain free intervals. Many patients

get relief while by assuming Trendelenberg position in which the patient

is on an elevated and inclined plane, usually about 45°, with the head

down and legs and feet over the edge of the

table. Incontinence.& pain on moving the sacrum are seen in some

patients.

Although a spinal perineurial cyst

involves a single nerve root at first, it may enlarge to the point where

it compress adjacent nerve roots as well.

It is difficult to prove that Tarlov

cysts cause symptoms in many cases because other findings that can cause

these symptoms (disc herniation, stenosis.) are usually found along

with the cyst on MR images or at surgery.

Surgery indicated only if they cause

progressive or disabling symptoms.

Percutaneous CT-guided drainage provides

good relief for several months in most patients but cysts recurs in

almost all. Although the cysts re-pressurize and the patients'

symptoms returned in most cases, this technique seems to be a quick and

simple way of at least attaining a pain-free interval and possibly a

complete cure in some patients.

Sacral laminectomy with microsurgical

cyst fenestration and closure with reinforced epidural fat or muscle

grafts and fibrin glue application is widely employed; lumbar drains for

cerebrospinal fluid diversion for several days postoperatively has also

been suggested.

Secondary (False) arachnoid

cysts:

Arachnoid cysts that are not congenital have

been termed secondary or false cysts. I feel a brief mention of these

acquired cysts is appropriate in this section of developmental cysts.

Such cysts represent accumulations of

CSF resulting from postinflammatory loculation of the subarachnoid space in

patients with head injury, infection, or ICH. The cyst membrane may also

be composed of arachnoid, but in addition, inflammatory cells and

hemosiderin deposits may be present and it is difficult to fenestrate

these cysts.

Lepto meningeal cysts associated with

growing fractures in children are rare. The physiologic brain growth and

CSF pulsations contribute to cyst herniations through a dural rent.

Treatment includes primary repair of the dural rent and the bony defect.

2) EPENDYMAL

CYSTS:

|

These rare cysts arise due to

the inclusion of ependymal cells in the substance of the

brain. They may also originate from ectopic glial tissue present

in the subarachnoid space. Ependymal cysts are common in

oral-facial-digital syndromes.

These later take up a secretory

function resulting in the formation of a cyst. These are

intracerebral and usually adjacent to the ventricles with which they

may occasionally communicate.

The gross appearance is usually

indistinguishable from an arachnoid cyst. Microscopically, the cyst may

be lined by cells resembling ependyma in some places. They may bear

cilia. Ultrastructural studies confirm the neuroepithelial origin of

these cysts.

|

|

|

|

Frontal

ependymal cyst

|

|

Colloid cysts of the third ventricle have also been

termed neuroepithelial cysts. Cysts in the fourth ventricle which

were lined by cells similar to ependymal cells and cuboidal cells

resembling the epithelium of the choroid plexus have been reported.

Similar choroid plexus cysts may also occur in the third ventricle and

block the foramen of Munro.

Excision is required in only the

symptomatic cases. The rest may be followed up periodically.

3)

RATHKE'S CLEFT CYSTS:

These cysts were first described by

Martin Heinrich Rathke (1793–1860), a German anatomist. Rathke's cleft

cysts are benign, nonneoplastic lesions that are believed to be remnants

of Rathke's pouch, which is the superiorly directed evagination from the

stomadium of the 4 week old human embryo; all but the cranial portion of

the pouch becomes obliterated by week 7 of gestation. The anterior wall

of the remaining cavity becomes the anterior pituitary, while the

posterior wall becomes the pars intermedia of the gland.

Rathke’s cleft cysts are primarily

intrasellar and are found in 13% to 23% of postmortem examinations.

Rathke's cleft cysts are uniloculate and

thin-walled and contain watery to mucinous fluid. Light microscopy of the

lining shows goblet, ciliated and, to a lesser extent, secretory cells of

anterior pituitary type. The finding of ciliated epithelial and mucous

secreting cells in a pituitary gland are pathgnomonic for Rathke's cleft

cysts.

Radiologically, they may mimic

craniopharyngiomas or as cystic pituitary adenoma.

Plain skull radiographs do not, usually,

reveal a enlarged sella turcica. In patients with symptomatic Rathke's

cleft cysts , plain skull radiographs commonly demonstrate findings of an

abnormally configured sella, which varies from slight asymmetry of the sellar

floor to massive erosion. In some patients, intrasellar and/or

suprasellar calcification is observed.

CT reveals an hypodense cystic mass

lesions arising from the pituitary fossa, without enhancement.

MRI shows cystic lesions with long T1

and long T2 although sometimes intrinsic paramagnetic substances may

produce T1 and T2 shortening resulting in hyperintense T1 and hypointense

T2 lesions. Rathke's cleft cysts usually have a thin wall that may

enhance with gadolinium-based contrast material. Variability in the

gadolinium enhancement among individual cysts may reflect squamous

metaplasia in the wall or a peripherally displaced rim of pituitary

tissue.

Rathke's cleft cysts almost always

are homogeneous in signal intensity, whereas other lesions, such as

cystic craniopharyngiomas and hemorrhagic adenomas, more frequently have

heterogeneous signal intensity.

These cysts are rarely symptomatic and

are usually incidental findings on imaging studies. Occasionally, they

cause symptoms by causing pressure on adjacent structures such as the

optic nerves and the pituitary gland causing visual problems, loss of

pituitary function, hypothalamic dysfunction and headache when they grow

in the suprasellar space. A Rathke's cyst may occasionally be associated

with a pituitary adenoma. Partial excision of the cyst wall and drainage

should result in cure: only a small percentage of such cysts recur.

4) PORENCEPHALIC CYSTS:

|

More appropriate term may be

'hole in the brain'

Porencephalic cysts,

characteristically, communicate with the ventricles or subarachnoid

space and are covered on the outside by arachnoid.

These are congenital (primary)

intracranial cysts and may arise as a leptomeningeal cyst.

It is possible that a failure

of development of a part of the cerebral mantle may result in a

cyst.

In addition to their congenital

origin, porencephalic cysts may also arise as a result of trauma

specially during birth or infancy when following loss of cerebral

tissue adjacent to the ventricles a cyst forms and communicates with

the ipsilateral dilated ventricle.

Puncture porencephaly is the

development of a cystic cavitation along the track of a ventricular

needle, manifesting in course of time, following rise in intracranial

pressure due to nonfunctioning of the shunt in cases of

hydrocephalus.

|

|

|

|

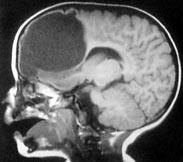

Porencephalic

cyst

|

|

This may also follow prolonged

ventricular drainage or repeated ventricular punctures.

Surgical excision may be

considered in cases where these cysts are found to be the cause of

intractable epilepsy. The area of excision should include the surrounding

gliosed cerebral tissue as well.

5) Other

developmental cysts are discussed elsewhere.

They are, Colloid cyst of the third

ventricle, Dandy

Walker cyst, and Epidermoids,

Dermoids, & Neuroenteric cysts.

|