|

Extradural hematoma (EDH) can be the most satisfying case

for a neurosurgeon and constitutes a major source of preventable

mortality in the head injured.

Epidemiology:

It occurs in all age groups, but mostly in under the age of

40 years and commoner in males. It is the most common post-traumatic

intracranial hematoma in children and follows SDH and ICH in adults. 10%

of fatal injuries in Glasgow autopsy series, 1-4% of imaged

craniocerebral trauma, and less than 2% of admitted craniocerebral trauma

have EDH.

Aetiology:

It is the result of an impact injury most common in

road traffic accidents, assaults, and fall from a height. Occasionally,

it may present as a post operative event or as a result of bleeding from

a dural AVM.

Pathophysiology:

The potential extradural space needs to be stripped off the

inner table before the meningeal vessels bleed. In children under 3 years

and in the older age group, the dura is adherent to the inner table and

hence the EDH is less frequent.

In more than 50% of EDHs, the source of bleeding is a

ruptured middle meningeal artery. In 33%, it is a ruptured middle

meningeal vein. The rest is from venous sinuses and diploic veins. The

extravasated blood separates the dura from the bone, leading to

detachment of further vessels thus aggravating the bleeding; the

stripping do not cross the suture lines. Over 80% of them are associated

with a fracture.

In 67%, the involved site is temporo-parietal region, and in

about 10%, the site is frontal. Occasionally it is bilateral.

Posterior fossa EDHs are uncommon, but the

clinical deterioration is rapid. A fracture at the region of transverse

sinus or a diastasis of the lambdoid or occipito-mastoid suture should

alert the surgeon. A collection of 15ml of blood in the subtentorial

space results in severe functional disturbance. Obstructive hydrocephalus

is an ever present possibility.

Clinical features:

|

The volume is not always directly proportional to the

severity of the clinical symptoms. 25 ml of hematoma is considered

significant. The clinical picture depends on location, rapidity

of hematoma formation, associated intradural and other injuries, and

internal decompression through fractures (blood & CSF

leakage).

The classical triad of head injury with lucid interval,

ipsilateral mydriasis and contralateral paresis occurs only in 18% of

cases and mainly in hematomas of the parieto-temporal hematomas.

Often, the clinical picture is a combination of the above.

There are no definite symptoms of epidural hematomas. The

clinical course may the same in acute SDHs, ICHs, and temporal and

frontal contusions.

|

|

In acute

EDHs, the frequency of the clinical presentations is as follows:

|

|

hyperacute

course (up to 10 hours)

|

10%

|

|

acute course

(up to 24 hours)

|

38%

|

|

short LOC

followed by lucid interval (classical type)

|

18%

|

|

irritability,

headaches, nausea

|

84%

|

|

GCS<7

from the onset with progressive deterioration

|

31%

|

|

ipsilateral

anisocoria

|

50%

|

|

contralateral

anisocoria

|

4%

|

|

contralateral

hemiparesis

|

62%

|

|

ipsilateral

hemiparesis (kernohan's phenomenon)

|

3%

|

|

|

In subacute or chronic types, the lucid

interval may last for days and weeks.

In children, seizures, vomiting, irritability,

lethargy are common. The onset of symptoms may be delayed, but

deterioration may be rapid. Fracture is uncommon. Blood volume lost to

the extradural space in an infant may be enough to produce a clinical

picture of shock.

|

Investigations:

X-rays of the skull may reveal a

fracture, suggesting the site of the EDH.

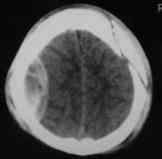

CT scan is the investigation of

choice. The minimal volume required for visualization in CT is about

25ml. Initial CT may be negative in about 30% of cases. The hematoma is

seen as a biconvex, hyperdense, nonenhancing extraparenchymal lesion.

Heterodensity (Glacier effect) suggests active/

fresh bleed.

|

|

|

Hypodense

bubbles within the hematoma suggest venous tear.

|

Biconvex EDH-CT

|

|

The hematoma may become isodense in about 2 weeks.

Obliteration of cerebral sulci may give a clue.

A chronic EDH may reveal a contrast enhancing periphery.

Associated parenchymal injury, and a midline shift of

>8mm suggest a bad prognosis.

|

|

|

MRI scans show better delineation of the pathology. The displaced

dura

|

Fracture

& contra-coup EDH-CT

|

|

appear as a thin

low signal intensity between the hematoma and brain.

Ultrasound is

useful in children with open fontanels and cost effective during

conservative treatment and follow-ups.

Management:

Non operative management may

be tried when an EDH is an incidental finding and small (<1cm) with

no suggestion of raised ICP or focal deficit.

|

|

|

Close

observation with serial CT scanning is a must.

|

Post.fossa EDH-CT

|

Prolonged hospitalization may be required.

In an emergency when clinical symptoms develop rapidly and

an urgent CT scanning is not available, exploratory burrholes

on the site of fracture or soft tissue injury and/or in the temporal

region on the side of pupillary dilatation are carried out.

Frontal and parietal burrholes may be done if the other burrholes

do not reveal a clot. It is advised to explore the opposite side as

well. However, burrholes usually do not lead to radical removal of

the EDH.

A craniotomy allows radical removal of the EDH

and control of the bleeding; the dura may be opened if associated SDH is

suspected. Bony decompression is advised by some surgeons. Some surgeons

prefer to leave a drain. A ventricular drainage may be required in

posterior fossa lesions.

Massive (malignant) cerebral edema following

evacuation is assumed to be due to loss of cerebral autoregulation. It is

usually associated with delayed evacuation and very difficult to treat.

Post operative intensive management with attention to

metabolic, respiratory, and infective complications associated with

prolonged unconsciousness determines the final outcome. ICP monitoring

helps to detect reaccumulation of the EDH.

Prognosis:

It depends on the extent of secondary brain injury and

associated injuries. The nature of the first aid given and the timing of

the surgery determine the prognosis. The longer the period of lucid

interval, the greater are the chances of full recovery. GCS at the

time of surgery, and the volume of EDH also determine the

outcome.

The overall mortality ranges from 20-40% in various series.

Children do better. Faster transportation of the head injured, earlier

recognition of the clot, improved neurosurgical services, and the

availability of CT scans have greatly improved the prognosis.

|