|

Cranial

dysraphism includes a wide variety of cystic lesions, commonly known as,

‘encephaloceles’, and other midline lesions of the skull that are not

cystic, such as, rudimentary encephaloceles, congenital defects of the

scalp or skull, and congenital dermal sinuses. Neuroembryology,

pathogenesis and prenatal diagnosis are discussed elsewhere.

Encephaloceles:

An

encephalocele is a cystic congenital malformation in which central

nervous system structures, in communication with cerebrospinal fluid

pathways, herniate through a defect in the cranium. It is the result of

failure of the surface ectoderm to separate from the neuroectoderm. This

results in a bony defect in the skull table, which allows herniation of

the meninges(meningocoele) or herniation of brain tissue in addition(a meningoencephalocele).

Unlike spinal dysraphism, encephaloceles form after neural tube closure.

Those

lesions without a cystic component, such as congenital absence of the

scalp or skull, could occur at an even later date.

Incidence:

When

compared to the spinal dysraphism, they are one tenth less common.

Posterior location is common in the west, and anterior location in south

asia. In India, the occipital encephalocoele is certainly the commoner of

the two. The reason for the geographical differences is unknown.

Most

cases of encephalocele are sporadic, with only a few patients having a

positive family history for neural tube defects involving either the

cranium or the spine. Posterior lesions are more common in females.

The

role of other factors, such as nutrition, folic acid, and increased body

temperature of the mother, are not known because the rarity of this

lesion makes it difficult to obtain the appropriate epidemiological

information.

Anterior

encephaloceles can be classified into frontal, sincipital (those located

about the midface- nasoethrnoidal, nasal, nasoorbital, nasopharyngeal,

buccal), and basal (those located at the base of the skull). Almost all

of these lesions contain neural tissue and thus are meningoencephaloceles.

The neurological outcome with most anterior lesions is normal and

hydrocephalus is unusual, but the associated craniofacial disruption can

vary from minimal to massive which include hypertelorism, orbital

dystopia, elongation of the nose and other stigmata of midline or lateral

facial clefts.

The

most common location is near the midline posteriorly, in the occipital or

suboccipital region, their size, whether there is neural tissue, and how

much neural tissue is contained within the lesion have overwhelming

bearing on outcome. Anterior and middle fossae are frequently deformed

and a Chiari malformation is a frequent association. Torsion of the

spinal cord and brainstem, asymmetry of the hemispheres, ventricular

anomalies and fusion of the thalami may occur secondary to herniation of

the brain into the encephalocoele.

Cranial

meningococles may rarely occur in the temporal region as a result of a

defect in the development of the first branchial arch.

Clinical

Features:

Most

often, they present as a midline cystic mass of variable size and shape,

and usually translucent, with variable amounts of solid tissue. It may be

reducible and exhibits a cough impulse.

A

basal lesion may protrude through the superior orbital fissure causing

proptosis or may herniate through the cribriform plate or sphenoid sinus

into the nasal cavity or nasopharynx, causing nasal obstruction.

Occasionally they rupture leading to CSF leak and recurrent meningitis.

Other

associated brain abnormalities that may occur in isolation or as part of

genetic or nongenetic syndromes include spina bifida, agenesis of the

corpus callosum, Arnold-Chiari II malformation, Dandy-Walker

malformation, and brain migrational anomalies.

Neurological

deficits are uncommon. However, during follow up patients with occipital

encephalocoele may have ataxia, nystagmus, blindness, pyramidal tract

signs and mental retardation either alone or in combination. Associated

anomalies include cleft palate and congenital heart lesions.

Imaging:

|

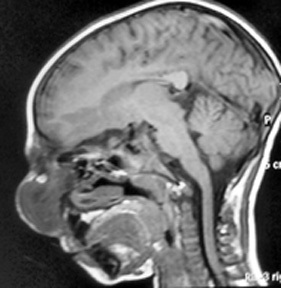

The

diagnostic study of choice is magnetic resonance imaging, supplemented

by magnetic resonance angiography if the vascularity and its relation

to the lesion need to be better defined.

With

sincipital and basal encephaloceles, computed tomography studies,

sometimes including three-dimensional reconstruction, may be of aid in

determining the need for, and planning the extent of, craniofacial

reconstruction.

Plain

radiographs are of limited value and are rarely obtained. After repair of

a posterior encephalocele, cranial ultrasound is an effective way of

following the size of the ventricles for development of progressive

|

|

|

|

|

Fronto-ethmoidal-sphenoidal encephalocele

|

Fronto-ethmoidal-sphenoidal encephalocele -MRI

(sagittal)

|

|

hydrocephalus,

which requires the placement of a shunt for diversion of cerebrospinal

fluid.

Treatment:

The

severity of additional anomalies must be considered as well as the size

of the lesions, amount of neural tissue within the sac, and degree of microcephaly,

and surgery may be withheld in selected cases.

Surgical

repair of the encephalocele involves, dissection of the sac and isolation

of the neck, inspection of the contents and replacement if possible,

excision at the neck and adequate closure of the defect at its neck.

Lesions

that are located above the torcular most often contain dysplastic neural

tissue, the resection of which does not influence neurological outcome.

Rarely, the cerebral tissue appears normal, in which case every effort should

be made to preserve it intact. This may require removal of the

surrounding bone so as to expand the cranial vault to accommodate the

volume of the neural tissue. Lesions below the torcular pose problems

similar to those found above, with the additional possibility of

inclusion of brain stem and cerebellum in the encephalocele. Large

lesions can be associated with a significant arterial supply and venous

drainage. The vessels therefore must be identified and coagulated before

being divided, and the sagittal, transverse, and occipital sinuses as

well as the torcular must be located before dural resection.

Intracranial

repair with craniofacial reconstruction is preferred in most sincipital

encephaloceles.

The

operative approach to a basal encephalocele is similar to that for the

sincipital type. Basal encephaloceles differ from sincipital

encephaloceles in that the bony defect is more posteriorly located on the

cranial base, especially involving the sphenoid. They are more likely to

contain structures such as the hypothalamus, pituitary gland and stalk,

optic nerves, optic chiasm, and anterior cerebral arteries within the

herniation. In infants, the presence of a basal encephalocele may be

heralded by nasal obstruction. As the mass presents in the nose, it may

be mistaken for a nasal polyp, the biopsy of which can lead to

cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea.

The

differentiation between a polyp and encephalocele is that an

encephalocele pulsates, presents medially from the nasal septum, and

widens the nasal bridge, while a polyp does not pulsate, is located

laterally, emanates from the turbinates, and does not widen the nasion.

Any

associated hydrocephalus is treated by a shunt procedure before the

encephalocoeie is excised. Following a shunt the encephalocoeie becomes

smaller, the closure of the defect becomes easier and the postoperative

risks of wound breakdown and CSF leak are minimized.

A

water-tight closure of the dural defect is achieved, using a graft if necessary.

A large defect in the bone may require repair.

Postoperatively

a careful watch is kept for evidence of raised pressure as a result of

hydrocephalus. Occasionally, in the immediate postoperative period the

intracranial pressure may rise very rapidly over a few hours and result

in a fatality unless recognized and treated energetically. If there is

evidence of rising intracranial pressure, the immediate postoperative

period is tided over by ventricular punctures. Some of these cases

require a shunt procedure postoperatively. Anticonvulsants are routinely

used. In occipital encephalocoeles, the outcome depends on the amount of

brain in the herniated sac, as well as the presence or absence of

hydrocephalus. A third of the patients develop normally, another third

are educable with moderate retardation and physical defect. The remaining

third are left with severe deficits. The prognosis in anterior

encephalocoeles is excellent.

Rudimentary

encephaloceles are midline lesions that are usually found at the vertex

and are associated with various skin changes, which can include cutis

aplasia, abnormal hair and hair pattern, telangiectasia, excessive

fibrous tissue, and dysplastic glial elements.

The

dysplastic skin is removed for cosmesis as well as to eliminate the local

irritation and pain that can accompany these defects. In lesions with

intracranial connection, intracranial exploration is avoided.

A

congenital dermal sinus is most likely to be found in the occipital

location, and often associated with a dermal inclusion cyst, which may

lie extradurally or, if it is intradural, may be located within the

cerebellum, fourth ventricle, or cisterna magna.

Chiari malformations are

discussed elsewhere.

Anencephaly:

Anencephaly results from failure of neural tube

closure at the cranial end of the developing embryo. Absence of the brain

and calvaria may be partial or complete. The brain is represented by a

dysfunctional mass of nervous tissue, which includes the primitive brain

stem and a few cranial nerves, which may be exposed or covered with skin.

Parts of the brain stem and spinal cord may be missing or malformed.

Failure of the neural groove to form into a tube, or gain a covering of

mesoderm or ectoderm, results in exposure of the brain and its ultimate

degeneration. Most of these fetuses are stillborn, but some may

occasionally survive for a few hours. The fetus has a partially destroyed

brain, deformed forehead, and large ears and eyes with often relatively

normal lower facial structures. Anencephaly and spina bifida are the most

common type of dysraphism. Familial occurrence can be high.

|